- Home

- Introduction

- Website News

- Postscript Magazines

- British History

- Company History

- British History National Cash Register Co. Ltd., 1896 - 1900

- NCR Films

- NCR Vintage Products

- Divisions

- NCR Newscast Tapes.

- Personalities

- The National Cash Register Company Ltd. 1896-1900

- Circuit News - Field Engineering

- Vintage Cash Register Service Aids2

- Supplies

The Inventor of the Cash Register 1879

James Ritty

It was James Ritty, -an obscure Dayton cafe owner, in collaboration with his brother John, who invented a machine that for the first time offered protection for the retail merchant. By putting indicators, that is, tablets registering the amount of a sale, in the machine he made it possible for the customer to check or audit the amount of his purchase. Such was the chief function of the pioneer cash register, destined to revolutionize the financial aspect of retail merchandising the world over.

When Ritty invented the cash register in 1878 he fitted into what might be termed the pattern of the inventor. As various historians of invention have pointed out, many of the men who have contributed notably to mechanical progress came not from within, but from without, industry. Cartwright, who invented the power loom, was poet and clergyman. Whitney, the cotton gin inventor, was a teacher who never had the slightest connection with cotton production. Howe and Singer, pioneers of the sewing machine, probably did not see the inside of a clothing factory until long after their patents were in use. Westinghouse was not a railway employee yet he devised the air brake. Fulton of steamboat fame and Morse, father of telegraph, were artists. Bell was a teacher of the deaf long before he transformed communication with the telephone. Thus it came about that James Ritty took his humble place in this gallery of giants of invention. He was a cafe owner whose primary purpose in creating the first cash register was to protect the cash receipts in his business.

James Ritty was one of five brothers. Their father, Leger Ritty, emigrated from Alsace Lorraine and settled in Dayton, Ohio. Leger Ritty was a dispenser of drugs made of herbs. He established an office. in the southwestern section of Dayton and built up a considerable practice. During a cholera epidemic "Dr." Ritty, as he was known, compounded remedies that helped to combat the disease.

Three of the Ritty brothers Sebastin, John and James were of an inventive turn of mind. Sebastin took out a number of patents on farm implements. John, ultimately to be associated with James in the invention of the cash register, was a mechanic by trade and carried on the inventive tradition of the family. Among other things, he patented several machines for the hulling of green corn and set up a canning factory in which they were used. He also operated a restaurant and. cafe. There is a story, still current in Dayton, that his ingenuity was revealed in a unique device. He piped water to all the tables in his restaurant and used the water power to operate motors which rotated palm-leaf fans for the comfort of his patrons in hot weather.

Hence James Ritty, who was the youngest of the brothers, grew up in an atmosphere that encouraged invention; His association with invention, however, was purely accidental. Although trained as a mechanic he forsook work with his hands and opened a cafe variously known as "No.10" and "The Empire" in a three-story building at 10 South Main Street in Dayton.

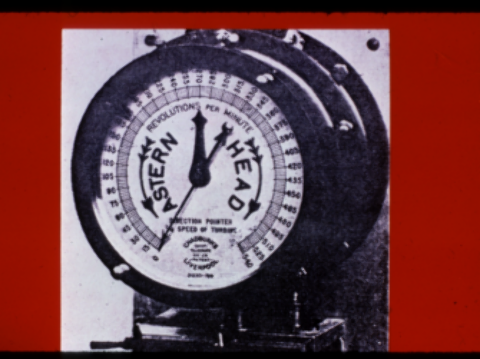

Ritty brooded so much over the peculations in his business that he suffered a breakdown and was obliged to take a vacation trip to Europe. His travelling companion was Captain Bogardus, a famous expert shot, who was to give exhibitions of his marksmanship abroad. Now developed one of those incidents that chart the course of invention. Having been trained as a mechanic Ritty became interested in the machinery of the ship. An agreeable and companionable fellow, he made friends with the Chief Engineer on the eastbound voyage. Soon he had the run of the engine room.

One day he stood fascinated before the automatic mechanism that recorded the revolutions of the ship's propeller shaft. With his thoughts still fixed on the losses in his cafe and how to circumvent them, he had an inspiration. To himself he said:

"If the movements of a ship's propeller can be recorded there is no reason why the movements of sales in a Store cannot be recorded. There is a great field for a machine that can do this work."

From that inspired moment, amid the din and clash of a ship's engine room, the idea of the cash register began to take shape in Ritty's mind. He became so obsessed with the thought that he cut short his stay in Europe and returned to Dayton. He confided the idea to his brother John. Together they began to work on a machine that was to make mechanical history. Born as a crude mechanism in the dawn of mechanization, the principles of the cash register were as logical in conception and as unerring in purpose as the telephone and the automobile.

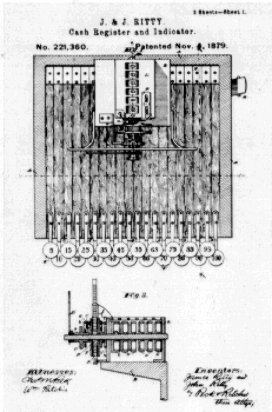

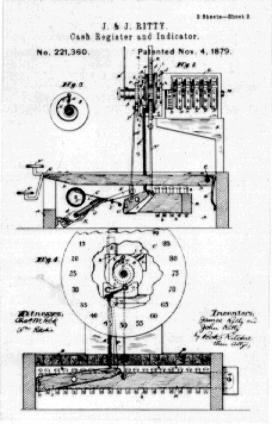

The first model had two rows of keys across the lower front of the machine. Pressed down, each key represented the individual amount of money to be recorded. The sales were registered on a face resembling the face of a wall clock or a steam gauge. There was no cash drawer in this earliest effort. Although incomplete in many details, the machine was the first outpost in the long line of protection that the cash register was to give to the retail merchant in the years to come.

The Rittys then made a second machine resembling the first in all details with one exception. Instead of adding disks the brothers designed a series of adding wheels mounted in the back of the machine. This machine was patented November 4, 1879. It was the first United States patent ever issued for a cash register. Neither of these two models was put on the market

Apparently dissatisfied with their dial models, the Rittys now began a new line of development. Instead of the dial type of indication they substituted a tablet form which was still used on many types of cash registers until the late 1960s. The tablet indicators were small plates bearing the same money values imprinted on the top of the keys, and were connected with the indicators by vertical sliding rods. As a key was depressed the indicator rod, resting on the key, was elevated until the indicator showed through a glass-covered opening in the upper part of the machine.

This was an important advance because the exact amount of the sale was revealed to both clerk and customer. The indicator was one of the early fundamental features of the cash register which has continued in use to the present day. From the start it meant increased protection for the merchant because it shed the light of publicity on every transaction. There was still no cash drawer in the third machine which the inventors called "Ritty's Incorruptible Cashier." This type was not sold to the public.

This was an important advance because the exact amount of the sale was revealed to both clerk and customer. The indicator was one of the early fundamental features of the cash register which has continued in use to the present day. From the start it meant increased protection for the merchant because it shed the light of publicity on every transaction. There was still no cash drawer in the third machine which the inventors called "Ritty's Incorruptible Cashier." This type was not sold to the public.

The next machine came to be known as the paper roll machine. James Ritty mounted a wide paper roll horizontally above and across the keys inside the machine. Each key carried a sharp pin. When the key was depressed, its pin pricked a hole in the roll of paper just above the key. At the same time the paper roll would be advanced, or fed, one step. The result was that at the end of the days business the proprietor could remove the roll of paper, unroll the portion representing the day's sales, and count the holes in each column. If there were ten holes in the five cent column, then that would equate to having sales of 50 cents. Because the paper was moved one position after each sale the owner could look across the line and see exactly the value of each individial sale

The paper roll machine marked an epoch in the progress of the cash register. It was the first to be put on sale, heralding an output and an expansion that became the marvel of the machine age. More important was the fact that it was this model which came to the attention of John H. Patterson who bought three of the machines and installed them in his general store at Coalton, Ohio. These registers, sold to Patterson, were the first to be installed in a mercantile establishment. All previous sales had been made to bar and cafe owners. Fate must have been lurking about when the Patterson transaction was consummated. Before very long Patterson was to become the pioneer of cash register production and to make his name synonymous with its development and distribution.

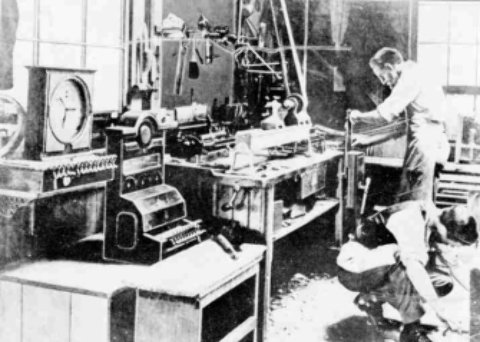

James Ritty launched the cash register business under the name of "James Ritty's New Cash Register and Indicator," in a little room over his cafe at 10 South Main Street. Apparently he did some advertising because registers were shipped to different parts of the country. The most distant order was from Duluth, Minnesota.

By October 1881 the infant cash register industry was beginning to emerge from its swaddling clothes. James Ritty needed more room so he moved to larger quarters. Here John Ritty was foreman. The factory force numbered ten men. Since the first machines that appeared on the market were largely constructed of wood, most of the employees were carpenters and cabinet makers, a trade which James Ritty had followed in previous years.

James Ritty encountered hard sledding in his efforts to build up the cash register business. He still conducted the cafe which demanded the major part of his time. In later years he confessed that he "simply could not direct the cash register business." Commenting on his failure he once said:

"If any one other than John H. Patterson had gotten the business, the cash register industry would never have been a success." Events prior to 1885 bore out this statement.

Following nearly two years of struggle, James and John Ritty sold their entire cash register business, including patents, to Jacob H. Eckert for $1,000.

James Bought the Pony Bar in Dayton and the bar has been preserved at Jay's Seafood Restaurant. [see Ritty photographs]

Footnotes

A James Bought the Pony Bar in Dayton and the bar has been preserved at Jay's Seafood Restaurant. Ritty photographs

B According to the 1918 Dayton Journal article No. 14 Closes Doors to Public, "Many years ago 'No. 10,' a saloon, high-class restaurant--and gambling palace was established at No. 10 South Main street by the late Simon Wagner and Jake Ritty. ...

A few years later 'No. 10' passed out of existence as such when the room was split in two, one portion being taken by Charles Zonars, the candy man, the other becoming 'The Wedge' saloon. ( Information provided by Helene Papanastassiou; Grandniece of Charles Zonars, "the Candy Man")